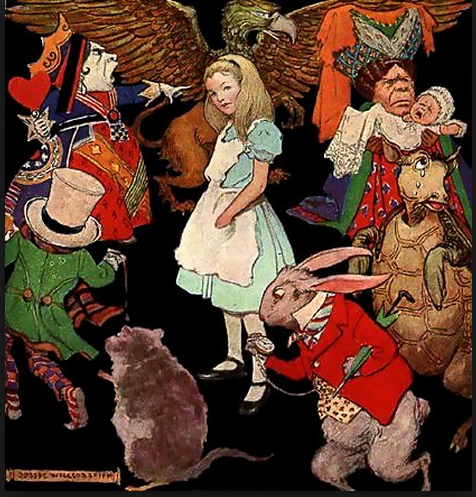

1923 Alice In Wonderland illustration by Jessie Willcox Smith. Wikipedia.org

Some researchers have found that illustration schools have historically had more women enrolled than men—as is the case currently in many if not most places—but this did not translate into more women in the industry, or anywhere near equality for them. For over a hundred years the field has consistently suffered from men saying that women have an equal shot at success as illustrators, when in fact this is not historically true at all.

In the nineteenth century, art school was seen as ladylike higher education—unlike, say, science. But few women could obtain a job as an illustrator, unless it was the lowest paid kind, such as the girls and women at Currier and Ives whose job it was to hand-colour the prints, or later, those who made illustrations for department-store catalogues, or even later, the Disney colorers of cels (transparent sheets of paper used in hand-drawn animation.) Women who aspired to something more had to freelance. Some did exceptionally well at it, but usually only on topics considered womanly—children, fashion, and home, which women were supposed to innately understand. Jessie Willcox Smith was lauded for her purported expertise in children—despite being childless herself.

In 1903 the Society of Illustrators (founded in 1901) elected two outstanding women as Associate Members: Elizabeth Shippen Green and Florence Scovel Shinn; then Violet Oakley, Jessie Willcox Smith, and Mary Wilson Preston in 1904. SI amended its constitution and allowed its (by then) 25 women to become full members in 1922, but few women ever served as administrators. (I’d like to thank librarian Marissa Hiller for the SI facts, and an article by Arpi Ermoyan in the SI Bulletin, Sept. 1979).

It bears mention that male SI members aggressively normalized a heavily sexualized playboy identity for themselves that did not begin to fade until about 1965. The famous annual SI Show, open only to male audiences, consisted of racy skits starring g-stringed artists’ models and the illustrators themselves. Members’ wives, many of them arts professionals, helped produce these shows, and the models—often aspiring actresses who received only a small honorarium for the Show work—found the “exposure” to be a career boost. Proceeds allowed SI to purchase their building, and later went to SI’s relief and educational funds.

In the early twentieth century the correspondence art schools solicited female students by telling them they could make as much as a man. Successful women like Smith did indeed, and are often held up as examples that it was a level playing field. But in fact, editorial illustration shows disproportionate domination by men, while women frequently were stuck with more poorly-paid spot illustration.

The conviction that women couldn’t relate to anything but feminine subjects persisted. In Canada in the mid-30s, Lela May Wilson—wife of an established illustrator, York Wilson (who had got himself blacklisted for arguing with a prominent art director)—posed as an illustrator and carted York’s manly portfolio round to other art directors. She was warmly received by one, who admired the portfolio and promised to give her work if any story came along requiring “a woman’s point of view”—but of course it never did, because in her words, “he found there were so few stories that could be illustrated by a woman!” (York Wilson: His Life and Work, Carleton University Press, 1997, 4-6.)

During the Depression and after World War II women were dissuaded from taking jobs away from men. The Society of Illustrators records show a decline in female applicants during the 1950s. Around 1970 one of the Society’s newsletters solicited statements from various illustrators about sexism in the industry. Answers were extremely varied—at least one woman illustrator denied it, while Diane Dillon—who always collaborated with her husband Leo, with their works signed by both—reported that people frequently assumed she was just his secretary.

It is not easy to draw a line between positive images of women and sexualized images of women. With suffrage and the advent of white-collar women’s work in the early 20th century, and many women’s own rejection of Victorian sexual prudery, illustrations of women ranging from emancipated sporty to downright provocative were made for and were heartily appreciated by women consumers.

Some of those illustrators of pretty and sexy girls were women (Nell Brinkley, Neysa McMein, Zoe Mozert). Scholar Maria Elena Buszek has demonstrated that the main audience for Esquire Magazine and its Varga Girl pin-ups during WW II was in fact female. Women’s enjoyment of gender performance is still with us, and has contributed to the disagreements over whether sexy images of women are empowering or not.